Welcome to the eighth installment in our Evidence-Based Investment Insights series: "The Business of Investing."

In our last piece, “Get Along, Little Market,” we wrapped up a discussion about the benefits of diversifying your investments. This allows you to minimize avoidable risks, manage the unavoidable ones expected to generate long-term market returns and better tolerate market volatility along the way. The next step is to understand why we can expect positive investment returns and how to build your diversified portfolio to generate them.

With all the excitement and headlines over stocks and bonds, there is a key concept often overlooked: Market returns are a payment investors receive for providing the financial capital that feeds enterprise going on all around us, all the time.

When you buy a stock or a bond, your capital is ultimately put to work by businesses or agencies who expect to succeed at whatever it is they are doing, whether it’s growing oranges, running a hospital or selling virtual cloud storage. You are not giving your money away. You expect to receive your capital back, and then some.

Using financial capital and other resources, a business produces goods or services that can be sold for a profit. As providers of financial capital, investors expect a return on their money.

Investor Returns vs. Company Profits

Companies exist to generate profits. Government agencies exist to complete their work within a budget. Investors seek to earn generous returns. You would think that when a company or agency succeeds, its investors would too. However, a company’s success is only one factor that influences expected returns.

For example, even if business is booming, you cannot necessarily expect to reap the rewards simply by buying stock. Remember, by the time good or bad news is apparent it is likely already reflected in share prices.

The Fascinating Facts About Market Returns

So what does drive expected returns? Some of the most powerful factors spring from those unavoidable market-related risks we introduced earlier. As an investor, you can expect to be rewarded for accepting the market risks that remain after you have diversified away the avoidable ones.

Consider two of the broadest market investment options: stocks (equities) and bonds (fixed income). Most investors start by deciding what percentage of their portfolio to allocate to each. Regardless of the split, you are still expecting to be compensated for all of the capital you have put to work in the market. So why does the allocation matter?

When you buy a bond …

- You are lending money to a business or government agency, with no ownership stake.

- Your returns come from interest paid on your loan.

- If a business or agency defaults on its bond, you are closer to the front of the line of creditors to be repaid with any remaining capital.

When you buy a stock …

- You become a co-owner in the business, with voting rights at shareholder meetings.

- Your returns come from increased share prices and/or dividends.

- If a company goes bankrupt, you are closer to the end of the line of creditors to be repaid.

In short, stock owners face higher odds that they may not receive a return, or may even lose their investment. There are exceptions. A junk bond in a dicey venture may well be as risky as any stock holding. Stocks are generally considered riskier than bonds and have generally delivered higher returns than bonds over time.

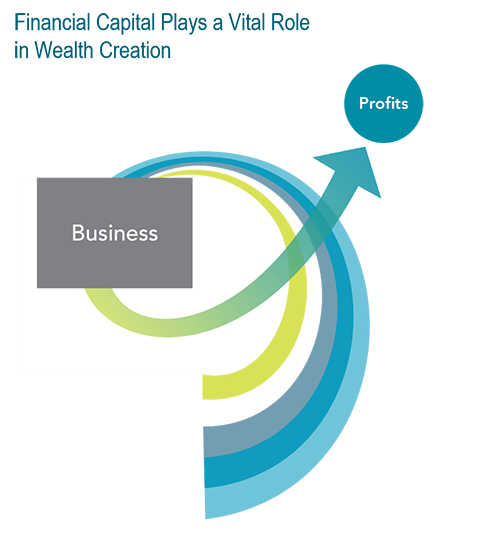

This outperformance of stocks is called the equity premium. The precise amount of the premium and how long it takes to be realized is far from a sure bet. That’s where the risk comes in. But viewing stock-versus-bond performance in a line chart over time, you see stock returns have a higher rate of growth than bonds over the long-run … but also have exhibited a bumpier ride along the way. Higher risks accompany higher returns in the results.

The data above illustrates the beneficial role of stocks in creating real wealth over time. Treasury-bills have barely covered inflation, while longer-term bonds have provided higher returns over inflation. US stock returns have far exceeded inflation and significantly outperformed bonds.

Your Takeaway

Exposure to market risk has long been among the most important factors contributing to returns. At the same time, we know there are additional factors contributing to premium returns. Next up, we’ll continue to explore market factors and expected returns, and why our evidence-based approach is so critical.